The 2022-23 Budget

Summary

In this brief, we provide an overview of the Governor’s package of public safety proposals, our assessment of these proposals, as well as recommendations and options for legislative consideration.

Governor Proposes $179 Million in 2022‑23 for Package of Public Safety Proposals. The Governor’s budget includes a total of $179 million General Fund in 2022‑23 (declining to $22.5 million annually by 2026‑27) to support nine different public safety proposals across multiple state departments. The goals of this package are to (1) reduce organized retail theft and mitigate harm on businesses that have been victims of such crimes; (2) reduce the presence of firearms, thereby reducing both violent crimes involving firearms and suicides; and (3) reduce other crimes, particularly drug‑trafficking by transnational criminal organizations.

Package Lacks Clear Objectives, Other Public Safety Goals Could Be Higher Priority. Overall, we find that the Governor’s package lacks clear objectives for achieving the intended public safety goals. We also find that the Legislature may determine that there are other public safety goals of higher priority than those put forward by the Governor, such as targeting the recent increase in some violent crimes—particularly involving firearms—rather than retail theft.

Two Proposals Appear Reasonable, Others Raise Concerns. Related to the Governor’s nine proposals, we find that two of the proposals—a proposed $2 million ongoing General Fund augmentation to support the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center and $5 million ongoing General Fund to maintain the Department of Justice Task Force Program—appear reasonable. We identify concerns with the remaining seven proposals. Specifically, we find that (1) the Board of State and Community Corrections grant program proposals would provide the administration with significant implementation authority, (2) details on the grants to small business victims of retail theft are not yet available, and (3) certain proposals may not be structured to achieve their desired outcomes.

Recommendations. We recommend the Legislature consider approving $7 million ongoing General Fund to support the two proposals that appear reasonable. For the remaining funding, we recommend the Legislature first consider whether public safety is a priority for additional funding relative to its other budget priorities. If public safety is a priority, we recommend that the Legislature consider how to allocate the remaining funding by determining its specific highest‑priority public safety goals, specifying clear objectives, and providing funding in a manner that ensures its goals and objectives are achieved. To assist the Legislature with its deliberations, we provide various options—such as those that expand upon existing programs or are based on research—that the Legislature could take to the extent it prioritizes addressing specific crime‑related public safety goals.

As part of his proposed budget plan for 2022‑23, the Governor proposes a package of nine different public safety proposals broadly aimed at reducing crime—particularly organized retail theft—and the presence of firearms and illegal drugs. This brief provides an overview of the Governor’s package of public safety proposals, some overarching issues for legislative consideration, and our assessment of the Governor’s proposals, as well as recommendations and options for legislative consideration.

The proposed budget includes a total of $179 million General Fund in 2022‑23 (declining to $22.5 million annually by 2026‑27) across multiple state departments to support the implementation of the Governor’s public safety package. Based on our conversations with the administration and review of budget documents provided by the administration, it is our understanding that the Governor’s proposed package is intended to address multiple goals. Specifically, the Governor aims to (1) reduce organized retail theft and mitigate harm on businesses that have been victims of such crimes; (2) reduce the presence of firearms, thereby reducing both violent crimes involving firearms and suicides; and (3) reduce other crimes, particularly drug‑trafficking by transnational criminal organizations. Figure 1 provides an overview of the specific proposals in the Governor’s public safety package, which we describe in more detail below.

Figure 1

Overview of Governor’s Proposed Public Safety Package

(In Millions)

|

Department

|

2022‑23

|

2023‑24

|

2024‑25

|

2025‑26

|

2026‑27 and Ongoing

|

|

|

Proposals Addressing Organized Retail Theft

|

||||||

|

Organized Retail Theft Prevention Grant Program

|

BSCC

|

$85.0

|

$85.0

|

$85.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Vertical Prosecution Grant Program

|

BSCC

|

10.0

|

10.0

|

10.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

CHP Organized Retail Crime Task Force Expansion

|

CHP

|

6.0

|

6.0

|

6.0

|

$10.5

|

$15.0

|

|

DOJ Organized Retail Crime Enterprises Program

|

DOJ

|

6.0

|

6.0

|

6.0

|

0.4

|

0.5

|

|

Grants to Small Business Victims of Retail Theft

|

GO‑Biz

|

20.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Proposals Addressing Firearms

|

||||||

|

Gun Buyback Grant Program

|

BSCC

|

$25.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

UC Firearm Violence Research Center

|

UC

|

2.0

|

$2.0

|

$2.0

|

$2.0

|

$2.0

|

|

Proposals Addressing Drug Trafficking and Other Crime

|

||||||

|

Counterdrug Task Force Program Expansion

|

CMD

|

$20.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

DOJ Task Force Program

|

DOJ

|

5.0

|

$5.0

|

$5.0

|

$5.0

|

$5.0

|

|

Totals

|

$179.0

|

$114.0

|

$114.0

|

$17.9

|

$22.5

|

|

Proposals Addressing Organized Retail Theft

Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer) established organized retail theft as a specific crime that involves working with other people to steal merchandise with an intent to sell it, knowingly receiving or purchasing such stolen merchandise, or organizing others to engage in these activities. Depending on the circumstances of the crime, people who commit organized retail theft may be charged with other related crimes, such as burglary, robbery, receiving stolen property, fraud, or conspiracy. Below, we describe the specific proposals in the Governor’s package intended to expand on the state’s efforts to address organized retail theft.

Organized Retail Theft Prevention Grant Program ($85 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $85 million annually from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 for the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) to administer a new competitive grant program to support local law enforcement agencies in preventing retail theft and enforcing theft‑related laws. Proposed provisional budget language specifies that priority “shall be given to localities that do not have a designated CHP task force and that have the largest increases in theft‑related crimes over a three‑year period based on the most recent available data.” According to the administration, this language is intended to prioritize grant funds for law enforcement agencies in the Fresno and Sacramento areas where the Governor proposes to establish two new California Highway Patrol (CHP) Organized Retail Crime Task Forces (ORCTFs), as discussed further below. (ORCTFs consist of CHP officers who collaborate with local law enforcement agencies and prosecutors in specified regions to support investigation and prosecution of organized retail crime.)

Vertical Prosecution Grant Program ($10 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $10 million annually from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 for BSCC to administer a new competitive grant program for district attorneys to fund vertical prosecution of organized retail theft. Vertical prosecution is a strategy in which the same attorney is responsible for all aspects of a case from arraignment to disposition. According to the administration, funding would be prioritized for district attorney offices that have attorneys dedicated to the existing and proposed CHP ORCTFs. The administration believes that vertical prosecution would provide for greater consistency throughout prosecution of cases and the opportunity for attorneys to develop expertise in prosecuting organized retail theft.

CHP ORCTF Expansion ($6 Million). In 2019, the state established three CHP ORCTFs that operate in the greater Bay Area and portions of Southern California. These three task forces are currently supported with $5.6 million General Fund annually, which is scheduled to expire in 2026‑27. The Governor’s budget proposes $6 million annually through 2024‑25 (increasing to $10.5 million in 2025‑26 and $15 million in 2026‑27 and ongoing) for CHP to make the three existing ORCTFs permanent and establish two new permanent ORCTFs in the Fresno and Sacramento areas. Due to CHP’s high officer vacancy rate, the proposal assumes that these new task forces will be operated by existing officers working overtime for at least three years. After that time, the new ORCTFs would be operated using dedicated staff rather than overtime.

Department of Justice (DOJ) Organized Retail Crime Enterprises (ORCE) Program ($6 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $6 million annually from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 (declining to $500,000 annually beginning in 2026‑27) for a new program to pursue ORCE investigations and prosecutions. Specifically, the proposed resources for the first three years would support 28 positions—15 positions to pursue ORCE investigations and 13 positions and legal resources to prosecute resulting ORCE cases. The ORCE investigators plan to focus on complex, multi‑jurisdictional organized retail theft crime networks for fraud, tax evasion, and other white‑collar crimes. These investigators would coordinate with federal, state, local, and retail partners as well as coordinate data collection and information. The annual funding after the first three years would support one sworn DOJ agent who currently participates in the existing CHP ORCTFs. (The position is currently funded with limited‑term funding.)

Grants to Small Business Victims of Retail Theft ($20 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $20 million one time for the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO‑Biz) to administer grants to small businesses victimized by smash‑and‑grab robberies or that have suffered damage caused during retail theft incidents.

Proposals Addressing Firearms

Gun Buyback Grant Program ($30 Million). The Governor’s budget provides $25 million one time in 2022‑23 to BSCC for competitive grants to local law enforcement agencies to support local gun buyback programs. Such programs typically provide individuals with a safe place to dispose of firearms, with no questions asked, and may provide a financial incentive to encourage people to bring in their firearms for disposal. Local law enforcement agencies receiving grants would be required to provide a 10 percent match for any awarded state funds. According to the administration, the intent of these local gun buyback programs is to safely get guns off the street and dispose of them as well as promote awareness of gun and youth violence.

University of California (UC) Firearm Violence Research Center (UCFC) ($2 Million). In 2016, state law authorized the creation of the UCFC at UC Davis to conduct research into the causes, consequences, and prevention of firearm‑related violence. In 2019, state law further directed the UCFC to develop education and training programs for medical and mental health providers on the prevention of firearm‑related injury and death—including suicide and homicide prevention strategies as well as intervention tools (such as gun violence restraining orders and mental health interventions). The Governor’s budget proposes a $2 million ongoing General Fund augmentation to support research conducted by the UCFC—increasing total General Fund support for the center from $1 million to $3 million. The proposed increase would support additional research and education topics. The UCFC indicates such topics could include researching the effectiveness of gun violence restraining orders and community violence‑intervention programs in preventing violence.

Proposals Addressing Drug Trafficking and Other Crimes

Counterdrug Task Force Program Expansion ($20 Million). The Governor’s budget provides a $20 million one‑time General Fund augmentation to the California Military Department (CMD) for its existing Counterdrug Task Force Program. This program, which currently receives $27 million annually in federal funds, provides support to local law enforcement agencies in areas known to have high levels of drug trafficking. The administration indicates that requests for assistance from local law enforcement have far exceeded CMD’s level of ongoing funding. Accordingly, the proposal would allow CMD to fulfill in 2022‑23 more of the requests it receives from local law enforcement.

DOJ Task Force Program ($5 Million). As of August 2021, the DOJ Task Force Program included eight task forces around the state. These task forces, which generally consist of a DOJ commander and various federal and/or local law enforcement participants, typically focus on more serious or complex criminal investigations—such as complex homicides or violent crimes, drug smuggling networks, or transnational gangs. Specific activities depend on the priorities of the task force participants, but generally focus on regional needs. These task forces are supported by state, local, and federal funds, with each task force participant’s employing agency typically paying for their participant’s salary and associated costs. For example, the state typically pays for the salary and associated costs (such as equipment) of the DOJ commander. The Governor’s budget proposes $5 million annually to support existing DOJ costs—not covered by other fund sources—that are associated with the department’s eight task forces. According to DOJ, these costs are currently supported by existing funding in its budget associated with vacant positions. (When positions approved in the budget go unfilled, the funding received by departments associated with the positions is often redirected by departments for other purposes.) According to DOJ, this funding will no longer be available as it expects to fill the vacant positions.

Overarching Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we identify two overarching issues for the Legislature to consider as it evaluates the Governor’s public safety package. Specifically, we find (1) the Governor’s overall plan lacks clear objectives for achieving the intended public safety goals and (2) the Legislature may determine that there are other public safety goals that are of higher priority than those put forward by the Governor.

Lack of Clear Objectives Makes It Difficult to Assess Governor’s Plan

As mentioned earlier, the Governor’s proposed public safety package is intended to achieve the goals of reducing crime—particularly organized retail theft—and the presence of firearms and illegal drugs. However, the Governor has not specified clear and specific objectives for achieving each goal. The absence of such objectives makes it difficult for the Legislature to determine the extent to which each of the Governor’s nine funding proposals would help meet the identified goals. Having clear objectives would also help facilitate future oversight of those proposals that the Legislature ultimately decides to approve. This is because the expected outcomes of each proposal should be tied to specific objectives. Otherwise, it is unclear how to measure the effectiveness of the proposals and determine whether they should be continued in the future.

For example, one of the Governor’s three goals is to reduce organized retail theft. The types of criminal activities related to organized retail theft can range from two people working together to steal merchandise and return it for store credit to a criminal organization that exploits marginalized people to steal on its behalf and sells the stolen merchandise through online marketplaces. As such, there are essentially numerous ways to potentially reduce organized retail theft. However, without clear and specific objectives it is difficult to determine which of the various criminal activities related to organized retail theft to target and to identify the specific actions to pursue with limited resources. For example, if the objective is to arrest individuals engaged in basic shoplifting or organized retail theft at a low level of sophistication, the use of video surveillance cameras could be an effective use of state resources. In contrast, if the objective is to dismantle criminal organizations engaged in organized retail theft, employing complex operations to uncover individuals who are running theft rings, as opposed to those they hire or exploit to shoplift for them, could be an effective use of state resources.

Other Public Safety Goals May Be of Higher Priority

While pursuing the specific goals of the Governor’s proposed public safety package may be worthwhile, there could be other goals related to public safety that the Legislature deems to be of higher priority. Below, we provide data related to recent crime trends and firearms to help the Legislature identify its highest‑priority public safety goals.

Crime Trends

DOJ collects data on crimes reported to law enforcement agencies throughout California. While these data underestimate the total number of crimes that have occurred (as they do not reflect unreported and certain types of crime), they provide useful metrics for tracking changes in crime rates over time. The most recent available year of data is 2020. However, analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) of preliminary data on certain crimes from four large cities (Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego, and San Francisco) covering the first ten months of 2021 gives an early indication of 2021 crime rate trends.

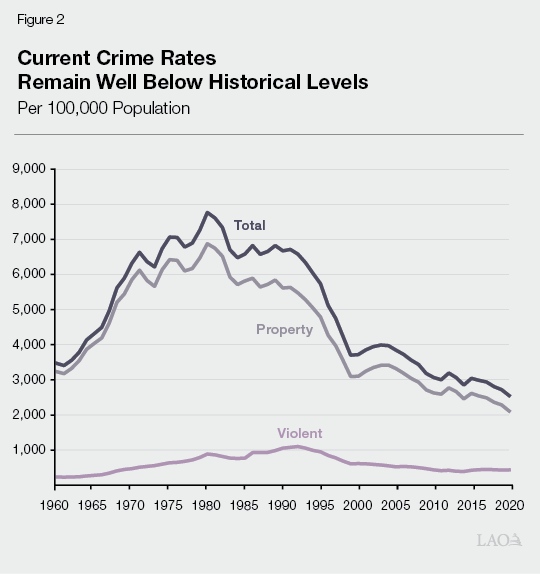

Crime Has Fluctuated During the Pandemic Yet Remains Well Below Historical Levels. During the initial phase of the COVID‑19 pandemic, California’s total crime rate—consisting of both property and violent crime—declined by 6 percent between 2019 and 2020—from 2,724 to 2,552 crimes per 100,000 residents. While the exact causes of this decline are not clear, experts have suggested it could be associated with businesses being closed and people staying home in response to public health orders. However, preliminary 2021 data suggest that the total crime rate may be returning to pre‑pandemic levels. From a historical perspective, such a potential increase in crime is occurring in the context of a major long‑term decline in crime rates. As shown in Figure 2, between 1980 (when the total crime rate peaked) and 2020, the state’s total crime rate declined by about 67 percent. Moreover, the property crime rate is at the lowest level ever recorded since reliable data collection started in 1960.

Limited Retail Theft‑Related Data Does Not Show Substantial Increases. There are no official crime statistics that report all retail theft separately from other types of crime in California. Specifically, while retail theft can occur in the form of burglary, robbery, embezzlement, and various other types of crimes—the numbers of these crimes that occur at retail establishments is not officially tracked statewide. However, shoplifting—a subset of retail theft—is tracked. DOJ data show a 29 percent decrease in shoplifting—from 226 to 161 per 100,000 residents—between 2019 and 2020. Some unknown portion of this decrease is likely associated with retail establishments being closed in response to COVID‑19 public health orders. Preliminary 2021 data indicate that total larceny theft—which generally includes stealing from retail establishments, non‑retail establishments, and private individuals—may be increasing in 2021, but as of October 2021 had not returned to pre‑pandemic levels.

We note that public concerns have been raised about the quality of reported shoplifting data, primarily due to retailers not reporting shoplifting due to a sense that individuals will not be sufficiently held accountable as a result of Proposition 47 (2014), which generally reduced the punishment for shoplifting. However, it is unknown what effect—if any—Proposition 47 has had on the quality of shoplifting data. (Please see the box below for more information on the effects of Proposition 47 on crime rates and crime data.)

Effects of Proposition 47

Proposition 47 Changed Sentencing Related to Shoplifting. Prior to the passage of Proposition 47 in 2014, stealing from a commercial establishment could be charged as commercial burglary, regardless of the value of merchandise stolen. Because commercial burglary is a wobbler, this meant that people who shoplifted (or attempted to shoplift) could be convicted of a felony, regardless of the value of merchandise involved. (Wobbler crimes can be punished as either a felony or a misdemeanor.) Proposition 47, created the crime of shoplifting, which consists of stealing (or entering a commercial establishment with the intent to steal) property worth $950 or less. Unless the person has certain prior convictions, the punishment for shoplifting is limited to a misdemeanor under Proposition 47.

Impact of Proposition 47 on Property Crime Unclear Based on Existing Research. According to research conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) on the impact of Proposition 47 on crime, there is some evidence that the implementation of the proposition increased property crime. While Proposition 47 was found to have no apparent impact on burglaries or auto thefts, PPIC concluded that it may have contributed to a rise in larceny thefts, particularly thefts from motor vehicles. PPIC found no evidence that Proposition 47 increased violent crime. However, researchers at the University of California, Irvine, concluded that Proposition 47 had no statistically significant effect on either violent or property crime.

Impact of Proposition 47 on Crime Data Unknown. Some concerns have been raised that reported crime statistics may not fully represent the impact of Proposition 47 on crime. Since statute and law enforcement practices typically require a higher threshold to support arrest and/or booking for misdemeanors as compared to wobblers, there are concerns that Proposition 47 limited the ability of law enforcement to arrest and book people into jail for the crimes it reduced from wobblers to misdemeanors. This has resulted in concerns that retailers have become less inclined to report such crimes because they do not think offenders will be held sufficiently accountable. However, the extent to which this is occurring is unknown.

Recent Increase in Motor Vehicle‑Related Theft. Between 2019 and 2020, thefts of motor vehicles increased by 20 percent (from 352 to 422 per 100,000 residents) and thefts of motor vehicle accessories (such as catalytic converters) increased by 26 percent (from 138 to 174 per 100,000 residents). Moreover, preliminary 2021 data show motor vehicle theft may be further increasing. We note that this increase in motor vehicle thefts was not unique to California. Preliminary 2021 data from 27 cities across the United States show a 14 percent increase in motor vehicle theft between 2020 and 2021.

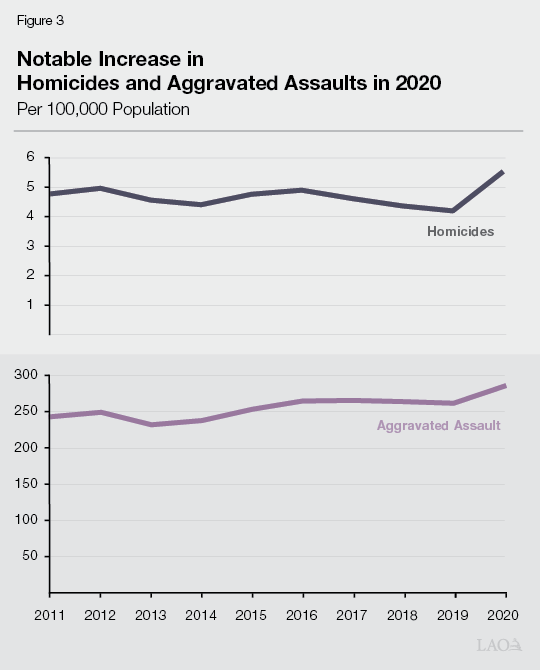

Notable Increase in Homicides and Aggravated Assaults. As shown in Figure 3, between 2019 and 2020, California experienced a 31 percent increase in homicides—from 4.2 to 5.5 homicides per 100,000 residents—the largest increase since reliable record keeping began in 1960. In addition, between 2019 and 2020, aggravated assault increased by 9 percent—from 262 to 285 crimes per 100,000 residents. Preliminary 2021 data shows that both homicides and aggravated assaults may be increasing again in 2021. These increases observed in California mirror nationwide trends. However, while the increases are concerning, we note that the rate of homicide and aggravated assault remain well below historical levels, similar to the total crime rate. Specifically, the 2020 homicide rate is 62 percent lower than its peak in 1980 and the 2020 aggravated assault rate is 55 percent lower than its peak in 1992.

Crime Rates Vary by Region. We note that statewide crime trends may not be representative of certain regions of the state. According to an analysis by PPIC, the 2020 violent crime rate in the San Joaquin Valley was more than double that in the southern and border regions. In addition, the property crime rate in the Bay Area was nearly double that in the Sierra region.

Potential Public Safety Goals Based on Crime Trends. To the extent the Legislature wants to prioritize crime reduction as proposed by the Governor, the above data suggest that the Governor’s specific goals may not be well targeted. For example, the limited data on retail theft does not appear to support a conclusion that retail theft is a significant problem in the state. Accordingly, the Legislature could choose to instead target homicide, aggravated assault, or motor vehicle‑related theft given the recent increases in these crimes. We note, however, that some experts and retailers report observing an increase in the criminal sophistication of shoplifters and the level of brazenness and violence involved in incidents of theft. This could warrant concern even if the total number of incidents has not changed. In addition, crime rates tend to vary by region and type of crime. Thus, while crimes like retail theft may not be of significant concern statewide, targeting such crimes in those areas where they are of significant concern could merit legislative consideration.

Alternatively, given that the total crime rate is currently quite low relative to historical standards, the Legislature may want to prioritize public safety goals not directly related to reducing crime. Such goals could include better addressing the mental health or housing needs of individuals involved with the criminal justice system.

Firearms

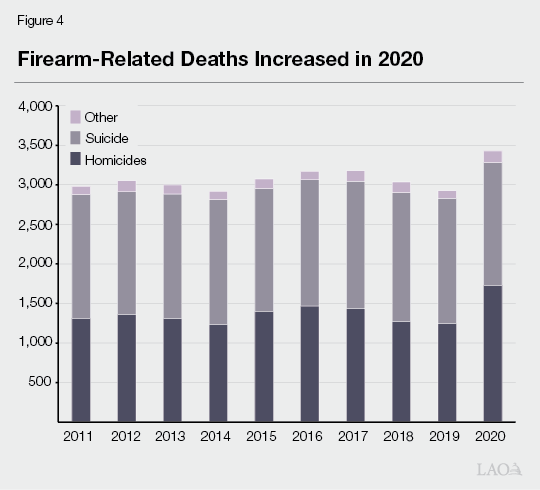

Recent Increase in Firearm Deaths. As shown in Figure 4, total firearm‑related deaths increased from 2,925 deaths in 2019 to 3,428 deaths in 2020—an increase of 503 deaths (or 17 percent). Of this amount, homicide firearm deaths increased from 1,246 deaths in 2019 to 1,731 deaths in 2020—an increase of 485 deaths (or 39 percent). In contrast, while there are slight fluctuations over the past decade, suicide firearm deaths were roughly the same in 2019 (1,586 deaths) and 2020 (1,552 deaths).

Increased Role of Firearms in Crime. As discussed above, California experienced a concerning increase in homicides and aggravated assaults between 2019 and 2020. In a July 2021 analysis of violent crime in large California counties, PPIC found that the share of crimes involving guns increased for homicides, aggravated assaults, and robberies.

Increase in Number of Armed and Prohibited Persons. The state’s Armed and Prohibited Persons System (APPS) identifies individuals who legally purchased or registered firearms, but subsequently became prohibited from owning or possessing them. These “armed and prohibited persons” include those convicted of felonies and some misdemeanors, found by a court to be a danger to themselves or others due to mental illness, or have a restraining order against them. From 2008 to 2021, the number of such persons more than doubled—from 10,266 to 23,598 individuals. Individuals are generally removed from this list when law enforcement reports they no longer possess their firearms (such as if a police department seized them).

Potential Public Safety Goals Related to Firearms. In view of the above data, the Legislature could consider prioritizing certain firearm‑related goals. Specifically, the Legislature could consider addressing (1) the growth in homicide firearm deaths or (2) the increase in the share of homicides, aggravated assaults, and robberies that involve firearms. Additionally, the Legislature could consider targeting the removal of firearms from armed and prohibited persons—particularly those who are prohibited due to mental illness or restraining orders. Research suggests that firearm prohibitions associated with mental illness may decrease violent crime and those associated with domestic violence restraining orders may decrease total and firearm‑related intimate partner homicides.

While the above section focuses on overarching issues for the Legislature to consider as it reviews the Governor’s overall public safety package, this section provides our assessment of the nine specific proposals within the proposed package. While we find that two of the proposals appear reasonable, we identify several concerns with the remaining seven proposals. Specifically, we find that (1) the BSCC grant program proposals would provide the administration with significant implementation authority, (2) details on the grants to small business victims of retail theft are not yet available, and (3) certain proposals may not be structured to achieve their desired outcomes.

Two Proposals Appear Reasonable

We find that two of the Governor’s public safety proposals—the $2 million augmentation for UCFC and the $5 million to maintain the existing task forces in DOJ’s Task Force Program—appear reasonable.

UCFC Research Could Help Inform Future State Actions in Addressing Firearm Issues. Firearm research has historically been constrained for decades—most notably by a prohibition on certain federal funding being used to advocate or promote gun control that has been in place since 1996. While this prohibition was relaxed slightly in recent years, it has generally left a gap in available research. As such, providing additional funding to UCFC could help address this gap by generating research that could be used by the state to determine how best to address firearm violence, injury, or other related issues effectively in the future. For example, UCFC indicates that it plans to research topics including identifying risk factors for future violence among authorized firearms purchasers and assessing the effectiveness of California’s firearm regulations in preventing firearm violence.

DOJ Task Force Program Facilitates More Complex Investigations With Both Regional and Statewide Benefits. Because each agency that participates in the DOJ Task Force Program typically pays for the costs of their own participants, there is incentive to ensure each regional task force focuses on investigating those crimes that are of highest priority to all participating members—likely the most pressing and/or complex criminal issues in the region. Each task force also benefits from the different resources and expertise of each participating agency, which allows the pursuit of more complex or multi‑jurisdictional cases. This collaboration allows for benefits or outcomes that may not have otherwise been achieved without great cost or if the participating agencies worked in isolation from one another. For example, a local law enforcement agency may not be able to afford to dedicate sufficient resources to pursue complex cases at the expense of more routine patrol activities. Moreover, since the state only supports DOJ’s costs associated with the task forces and not those of the participating agencies, the Governor’s proposal appears to be a cost‑effective method for the state and local governments to continue addressing more complex investigations that have both regional and statewide benefits.

As noted above, the state’s share of costs related to DOJ’s Task Force Program has been supported using funding associated with vacant positions that DOJ expects will no longer be available as vacant positions are filled. To the extent the DOJ Task Force Program is a priority, ongoing General Fund resources—as proposed by the Governor—would provide a stable source of funding. For budget transparency purposes, the Legislature may want DOJ to report in budget hearings on how it would use the vacant position funding currently supporting the DOJ Task Force Program if this proposal is approved and the vacant positions are not filled as planned. If these activities are not a priority for the Legislature, it could choose to reduce DOJ’s budget accordingly.

BSCC Grant Proposals Provide Administration Significant Implementation Authority

The Governor’s package provides the administration with significant authority in the implementation of the organized retail theft prevention, vertical prosecution, and gun buyback grant programs. While the administration proposes some budget provisional language with broad parameters, the specific implementation details would be left for BSCC to determine sometime after the budget is enacted. This is problematic as it significantly limits legislative input and oversight in various ways and could lead to unintended consequences, as described in more detail below.

Unclear How Funding Would Be Allocated and Used. Given that the Governor proposes to give significant authority to BSCC to implement the three grant program proposals, it is unclear how the grant funding would be allocated. According to the administration, after the budget is enacted, BSCC would convene Executive Steering Committees—composed of board members, content area experts, practitioners, and other stakeholders—and receive public comment in order to determine how funding will be allocated. As such, it is unclear how the proposed funding would be targeted or prioritized, whether there would be minimum or maximum grant amounts for a single applicant, and what metrics or outcomes would be collected. It is also unclear how the grant programs would be administered—such as what information would be required in a grant application and the criteria that will be used to determine which applications will be approved. Without this information, it is difficult for the Legislature to determine whether the proposed funding will be allocated equitably or accountably. For example, the Legislature may want to know whether BSCC would prioritize funding for applicants who are disproportionately impacted.

Difficult to Assess Whether Programs Will Be Effective. The lack of details on how the BSCC grant funding would be allocated and used makes it difficult for the Legislature to assess whether programs are structured in the most effective manner, what outcomes could be achieved, and how likely the Governor’s proposals are to be successful. For example, if the goal of the gun buyback program is specifically to reduce firearm crime‑related violence, research suggests that such programs are more effective if they require firearms be working in order to receive an incentive, prioritize the types of firearms used in crimes (such as newer firearms or semiautomatic pistols), and/or focus on the types of individuals or locations more prone to firearm violence. However, it is unclear whether BSCC will ensure the gun buyback program is structured effectively.

Similarly, the organized retail theft prevention grants to local law enforcement are competitive grants that can be used to support any activities that prevent retail theft or enforce theft‑related laws. The breadth of the existing language means that there are numerous possibilities for how the money ultimately could be used. A large portion of the funding could go to increasing law enforcement patrol of retail locations or to participate in task forces, instead of other activities such as the purchase of cameras or other technology that could achieve different outcomes and/or be a more effective use of limited‑term funding.

Supplantation of Local Funding Possible. The broad budget provisional language allowing BSCC to determine most implementation details could result in the supplantation of local funding. Law enforcement agencies and district attorney offices have an incentive to investigate and prosecute certain theft crimes—particularly if there is an ongoing local surge in such crimes—as this impacts the local economy and is frequently a concern of local constituents. This means that local agencies have a strong incentive to redirect resources internally to make the investigation and prosecution of such crimes a priority—even if the state does not specifically provide resources to do so. Accordingly, any state funds that are provided to local agencies under the Governor’s proposed package might not change the amount they would otherwise spend addressing such crimes. However, it is unclear whether BSCC will take steps to avoid this, such as requiring locals to provide matching funds. While it is possible that BSCC ultimately addresses this concern upon actual implementation, specific budget language to prevent it from occurring would increase the likelihood the monies are used effectively.

Lack of Detail on Grants to Small Business Victims of Retail Theft

The administration indicates the budget trailer language for the small business grant program is forthcoming and will provide more specific details on the allocation and use of the small business grant program monies. As a result, key questions about the program remain unanswered. For example, it is unclear what damages are eligible to be covered by the small business grants and how GO‑Biz will verify the amount of damages claimed by an applicant. This could mean that state funds could be used to pay for damages that may otherwise be covered by insurance or inadvertently reward retailers that took few precautions against theft. (For more information on this proposal, please see The 2022‑23 Budget: Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development Proposals.)

Certain Proposals Not Structured to Effectively Achieve Desired Outcomes

We find that some of the remaining proposals are not structured in a way that would achieve the Governor’s desired outcomes. In many cases, it is because the proposed programs may not be the responsibility of the most appropriate administrative entity or are not targeted appropriately. We discuss a couple examples below.

CHP ORCTF Expansion Could Face Challenges. If the state is interested in targeting organized theft coordinated by criminal gangs or networks, DOJ could be a better entity than CHP to administer such task forces. This is because DOJ has existing expertise in operating dedicated task force teams as well as managing task forces that consist of federal, state, and local partners. Additionally, DOJ employs both law enforcement investigative personnel as well as attorneys who can more easily work together to successfully investigate and prosecute cases. Furthermore, CHP currently does not have the ability to dedicate full‑time sworn officers to the two new ORCTFs proposed by the Governor due to a high vacancy rate. The requested funding would instead go to support overtime to pay for patrol officers to conduct increased enforcement in the initial three years. This may not be the most effective way to operate a task force as the patrol officers likely would not be able to fully focus on addressing retail theft in the same manner as full‑time dedicated officers. This could then impact the outcomes that can be achieved in the near term.

CMD Counterdrug Task Force Program Expansion May Not Address Overdose Deaths. The Governor’s proposal seeks additional resources to reduce opioid overdoses, as well as crimes and violence related to the smuggling and distribution of illegal drugs, by increasing CMD’s capacity to respond to local law enforcement requests for support. However, according to the administration, the vast majority of local law enforcement requests tend to involve targeting illegal cannabis cultivation and trafficking rather than illegal drugs linked to overdose deaths. Accordingly, as currently structured, the proposal is likely to have little effect on overdose deaths. Addressing illegal cannabis cultivation and trafficking is a reasonable statewide goal. However, if the state is interested in reducing overdose deaths, this proposal would likely not be an effective way to do so.

Consider Approving Proposals That Appear Reasonable

UC Firearm Violence Research Center and DOJ Existing Task Force Funding. Two proposals—totaling $7 million ongoing General Fund—merit legislative consideration relative to the Legislature’s overall budget priorities. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature consider approving the proposal to provide $2 million ongoing General Fund to the UCFC as the funding would address a research gap that could help the state determine how to effectively address firearm violence in the future. We also recommend the Legislature consider approving the proposed $5 million ongoing General Fund for the DOJ Task Force Program as the funding would maintain DOJ participation in its eight existing task forces. Such task forces can be cost‑effective ways of targeting more complex or multi‑jurisdictional criminal investigations that could have statewide benefits.

Consider Highest‑Priority Public Safety Goals for Remaining Funding

Determine Specific Goals. Given the concerns raised above with the remaining proposals in the Governor’s package, we recommend the Legislature first consider whether public safety is a priority for additional funding relative to its other budget priorities. If public safety is a priority, we recommend that the Legislature consider how to allocate the remaining funding ($172 million General Fund in 2022‑23) to address its highest‑priority public safety goals. This could include addressing specific aspects of crime (including those identified by the Governor) or other areas of public safety (such as better equipping the criminal justice system to respond to individuals with mental health needs). We also note that the Legislature could consider making changes to address public safety goals through the policy process.

Specify Clear Objectives and Weigh Trade‑Offs. Once the Legislature determines its goals, it will also want to specify the key objectives for each goal and identify specific actions to effectively achieve them. When considering the specific actions to pursue, the Legislature will want to weigh the relative trade‑offs. For example, certain actions could require ongoing—rather than one‑time—General Fund resources to operate effectively, placing ongoing fiscal pressure on the General Fund. Other actions could focus on providing resources to state entities, rather than local entities, in order to address statewide problems. Such actions could mean that local priorities may not be addressed. (In the next section of this brief, we provide options for the Legislature to address crime‑related public safety goals.)

Ensure Goals and Objectives Are Achieved. Regardless of whatever actions the Legislature chooses to fund, it will be important to ensure that the funding is provided in a way designed to achieve its goals and objectives. This includes (1) ensuring that the appropriate entity receives the funding, (2) the funding is provided for clearly defined purposes, (3) there are specific guidelines on how the funding can be used or allocated, and (4) the expected outcomes are clearly tied to key objectives. Additionally, the Legislature will want to ensure that it has sufficient oversight over the use of any provided funding. This can occur in various ways, including requiring regular reports on how the funding has been used or evaluations assessing the effectiveness of programs that received funding.

In this section, we provide various options that the Legislature could take to the extent it prioritizes addressing specific crime‑related public safety goals. Specifically, we discuss options including those that expand on existing programs and are based on research.

Options to Expand Existing Programs. The Legislature could consider expanding certain existing programs targeted at crime, particularly those programs with subject matter and/or operational expertise that could be leveraged to address problems more effectively and quickly than establishing a new program. Using an existing program can avoid duplication of effort as well as start‑up challenges (such as taking time to identify and develop stakeholder relationships or to create new operational processes) that would face a new program. Potential programs that the Legislature could expand include:

- Gun Violence Reduction Program to Reduce Number of Armed and Prohibited Persons. As previously discussed, APPS identified nearly 23,600 armed and prohibited persons as of January 2021. The 2021‑22 budget provided $10 million one‑time General Fund to DOJ’s Gun Violence Reduction Program for competitive grants to county sheriff’s departments to reduce the number of armed and prohibited persons by seizing firearms and ammunition from them. To the extent the Legislature would like to further reduce the number of armed and prohibited persons, it could provide additional funding to the Gun Violence Reduction Program and make other law enforcement agencies (such as city police) eligible for grants.

- Firearm Removal From Individuals Immediately When They Become Prohibited. Beginning in 2018, courts have been required to inform individuals upon conviction of a felony or certain misdemeanors that they must (1) turn over their firearms to local law enforcement, (2) sell the firearms to a licensed firearm dealer, or (3) give the firearms to a licensed firearm dealer for storage. Courts are also required to assign probation officers to report on what offenders have done with their firearms. Probation officers are required to report to DOJ if any firearms are relinquished to ensure the APPS armed and prohibited persons list is updated. To the extent the Legislature would like to limit growth in the number of armed and prohibited persons, providing funding to local law enforcement agencies and probation departments to ensure this process is followed can be effective as firearms would be surrendered at the time of conviction.

- DOJ Resources Targeting Complex or Organized Crime. If the Legislature wants to prioritize targeting organized crime or complex crime more broadly, it could provide funding for dedicated DOJ investigators and attorneys. DOJ special agents and attorneys have experience investigating and prosecuting complex cases and are best suited to addressing multi‑jurisdictional cases across the state. DOJ also has experience working with various local law enforcement agencies and other stakeholders. Finally, all staff are within the same agency which allows for easier coordination to successfully pursue such cases.

- DOJ Task Force Program to Address Crimes in Specific Jurisdictions. Certain crimes—including retail theft, motor vehicle‑related theft, or firearm violence—may disproportionately impact certain jurisdictions. If the Legislature prioritizes addressing this inequity, it could consider expanding DOJ’s Task Force Program (rather than expand CHP ORCTFs). This is because the task forces in DOJ’s Task Force Program operate regionally and consist of various law enforcement participants—including local law enforcement agencies—targeting the highest‑priority crimes in the area. Local law enforcement would have incentive to participate as costs would be shared with other task force participants and the crimes being investigated directly impact the local community. The state also benefits as it does not bear the full cost of addressing such crimes. (We note the Legislature could alternatively target funding directly to specific jurisdictions to address particular areas of increased crime.)

Research‑Based Options

The Legislature could consider options that research has found to be effective at reducing crime or certain types of crime. By pursing strategies that have been found to be effective, the Legislature would increase the likelihood that its desired outcomes are achieved. Research‑based options include:

- Research‑Based Interventions to Reduce Community Violence. A panel of criminology, law, and public health experts assembled by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice recently reviewed existing research to identify policies and programs found to reduce community violence without relying on police. Options identified include place‑based strategies (such as improving lighting in public places) and interventions to reduce substance use (such as expanding access to substance use disorder treatment). The panel also noted that policies or programs that mitigate financial stress on people, even from short‑term income shocks, can reduce both violent and property crime. For example, several studies have found that spreading nutritional benefit disbursements throughout the month as opposed to concentrating them at the beginning of the month (as is currently done for CalFresh) reduced thefts from grocery stores and violent crime in some cases. The 2021‑22 budget provided about $67 million annually for three years for the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Grant Program (CalVIP) to provide competitive grants to cities and community‑based organizations for evidence‑based violence reduction initiatives. In considering options for reducing violence, the Legislature could consider strategies that are different from those supported by CalVIP to avoid duplication.

- Research‑Based Tools and Best Practices to Address Retail Theft. To the extent the Legislature aims to reduce retail theft, there are a variety of research‑based tools and best practices that retailers can employ—often in partnership with local law enforcement—to deter and detect theft. For example, strategically placed surveillance cameras could help deter theft by increasing the likelihood that individuals will be identified. Accordingly, the Legislature could consider funding limited‑term grants to help retailers and/or local law enforcement invest in technology, infrastructure, training, or consulting services. This could help retailers better self‑protect from theft and improve the sharing of crime data and evidence between retailers and law enforcement.

Other Potential Options

The Legislature could consider various other options, such as those being tried in other jurisdictions. For example, some jurisdictions operate partnerships between retailers, police, and prosecutors through which shoplifters identified by retailers are required to complete a diversion program to avoid being prosecuted with a crime. Such programs can be designed to help people understand the harm that they cause when they shoplift as well as identify factors in their life that may be contributing to their behavior. This could help reduce shoplifting—whether by individuals working alone or by “boosters” hired by organized retail crime rings to shoplift on their behalf. In another example, at least one California city has used GPS tracking devices in “bait” cars in order to reduce motor‑vehicle thefts. Accordingly, the Legislature could consider funding a pilot to test these ideas.